Cold Air, Warm Hands

A night inside Hunts Point’s Fulton Fish Market, where the smell of the ocean clings to your clothes and skilled workers keep New York fed before sunrise.

The market hits you first with smell, not sight.

Even with the windows up, inching through the security line in the dark, there is already a faint briny funk seeping through the car doors, salt, diesel, thawing ice, and something older that has soaked into this place for decades. By the time the guard waves you through, the dashboard clock is stuck at an hour that feels wrong for being awake, let alone ready to work.

Inside, the parking lot glows under tall sodium lamps, the wet asphalt reflecting red brake lights in streaks like smeared paint. Trucks idle in every direction, white boxes with their back doors yawning open, exhaling clouds of cold air and the heavy breath of fish. Men in hoodies and beanies move like they are on rails, steering pallet jacks between bumpers with just inches to spare. Everyone seems to know the choreography. You step out of the car and the air hits immediately, colder than outside, somehow, and the smell jumps from faint suggestion to full assault.

The walk to the entrance is short but feels longer because you are moving against the grain. You are not hauling anything, not on a deadline. You are just a spectator with a camera and cold fingers. The big blue doors are scuffed, stamped with warnings, and when they swing open you cross an invisible line. Outside was night. Inside is a different time zone, ruled by ice, noise, and fluorescent light.

The first breath inside the main hall is like inhaling a whole ocean that has turned industrial. It is sharp and metallic, like wet pennies, but also fatty and rich from cut salmon and tuna. It settles into your clothes instantly. The cold is not the romantic kind of winter, it is mechanical, refrigerated cold that seeps up through the concrete and into your boots. The floor is slick with meltwater and scales, and every few steps you hear the crunch of stray ice underfoot.

The space is huge and strangely bright, a long spine of ceiling trusses running above rows of stalls stacked with boxes. Each unit has its own personality, its own little kingdom. At one stall, an electronic scale hangs from the ceiling, a blunt orange box with a glowing digital readout, chains leading down to a broad, stained metal pan. Whole fish spill over the edge, eyes clouded, bodies still shining under the fluorescent glare. Men in rubber aprons hoist them in and out with an easy, practiced swing, fingers moving without hesitation even when knives flash.

The sound never really stops. Pallet jacks beep and whine. Someone shouts an order over the din, numbers, species, weights, a kind of marketplace shorthand that bounces off the wet concrete walls. Cardboard tears. Plastic wrap crackles. A box drops with a muffled thud on ice. The drip of meltwater runs through all of it, underscoring the noise like a metronome. Every few minutes, the overhead speaker barks something unintelligible, and nobody looks up.

You linger near a stall with neat rows of long, red tuna loins lined up over crushed ice like a row of muscle laid bare. The man behind the table moves with a rhythm that could only come from repetition, pull a box, slice it open, inspect, nod, drag it into position. No theatrics, no performance for customers, this is wholesale, not a TV chef demo. The skill lies in what is unsaid, knowing how much pressure to put on the knife, when a fish looks right or wrong at a glance, how to read the eyes and the color and the firmness in seconds because there are twenty more boxes waiting.

A few units down, another stall glows with branded cardboard, shrimp from the Pacific, calamari from Seattle, neatly printed logos yelling PREMIUM at a volume that matches the clamor of forklifts. In front, two plastic tubs overflow, one with small whole fish buried in ice, tails and fins poking out, the other with uniform rows of pale bodies, their mouths slightly open like they are still catching their last breath. A worker in orange gloves moves between them, weighing, bagging, sealing deals with barely a pause. His hands never stop. His eyes flick constantly from scale to buyer to boxes stacked behind him like a wall.

The cold intensifies near these tubs, amplified by the proximity of so much ice. Your fingertips burn against the camera body. Every exhale shows up in front of your face, ghostly in the bright light. You realize that everyone else is dressed for this, layered hoodies under waterproof jackets, thick gloves, insulated boots that have long since sacrificed their original color to fish blood and slush. You, in comparison, are just visiting. They are built into the daily weather system of this place.

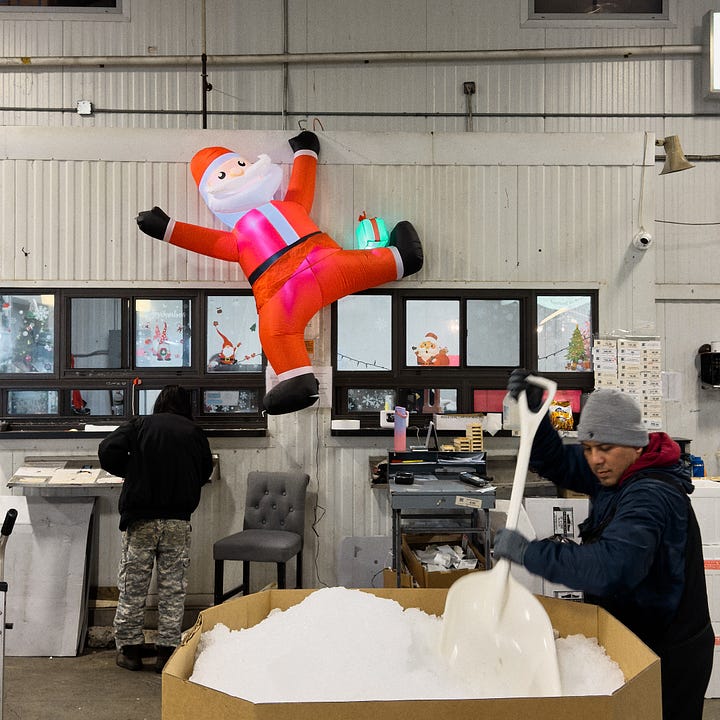

Around a corner, the market opens up even more, a long central aisle stretching out under a grid of lights that feels almost theatrical. The architecture hints at its history, industrial steel bones, catwalks, and stairs lining the sides, a second level where offices and break rooms perch above the chaos. From down on the floor, you see only flashes of life up there, someone leaning over a railing, a lit doorway where paperwork gets done while fish move below like currency.

In one corner office that doubles as a workstation, a faded American flag hangs from the ceiling, its length nearly reaching the floor. Below it, boxes crowd around a small desk cluttered with receipts, coffee cups, and a TRUMP VANCE campaign sign propped front and center. The politics of the place are not subtle. You get the sense this market is a world where people think a lot about fuel prices, regulations, and taxes, about what keeps trucks running and boats leaving docks, because that is what stands between them and a bad season. No one here has time for softened language. The sign says exactly what it says and then work continues.

Back on the floor, the smell has worked its way past your initial resistance. At first, it was an assault. Now it has become background radiation. Hints of specific species drift by as you move, sweet, clean notes from fresh salmon, deeper oily tones from mackerel and bluefish, something almost cheesy and sour near a bin of older scraps waiting to be hauled out. A worker scrapes scales from a table into a bucket with quick, flicking motions. Another hoses down a patch of floor, sending blood stained water streaming toward a central drain, where it disappears like it never existed.

What stands out most is how physical the labor is without being frantic. There is urgency, but not panic. Everyone has a route, a purpose. One person guides a pallet jack piled with boxes out toward a waiting truck. Another double checks invoices under the harsh light of a desk lamp, pen between gloved fingers. Deals happen in short, clipped exchanges, no receipts printed for show, just signatures on damp paper and a nod. It is skilled labor that almost never gets described that way outside these walls, work that demands knowledge of product, storage, timing, and people

The camera turns you into a kind of thief. You steal moments, a hand weighing fish on a hanging scale, a row of gleaming heads with mouths frozen open, the curve of a spine under crushed ice. One scale shows a weight on its digital screen, pounds and ounces ticking up as another fish lands with a wet thump in the metal pan. The numbers mean money to the people standing there. To you they are just proof that this world turns on precision, not romance.

Time drifts strangely inside the market. There is no natural light, only the relentless brightness of fluorescents overhead. At some point, you realize the tide is turning. Pallets that were full when you arrived now stand empty, cardboard torn and flattened in messy stacks. Trucks that were open for loading have their doors pulled down and sealed. Workers who were darting between stalls are now gathered near doorways, talking in clusters, the volume of their voices lower but easier to hear now that some of the machines have gone quiet.

You step back outside into the night, or what is left of it. The air feels different, less dense, too clean. Yet the fish smell is still there, clinging to your jacket, your hat, the cuffs of your jeans. Even in the cold, it rises gently every time you move. In the driver’s seat, you crank the heat, but that just warms the smell up, making it bloom inside the car. You roll the window down for a moment, then up again. There is no escaping it.

Driving away from Hunts Point, the market recedes into a blur of tail lights on wet pavement. The orange glow of the lot shrinks in the rearview mirror. It is still dark enough that the city feels half asleep, but you know entire restaurants will wake up with these fish, their menus shaped by the decisions made in those fluorescent aisles a few hours earlier. The labor you just watched is already dissolving into the anonymity of a plate in front of someone who will never think about how cold it was the moment that tuna hit the ice.

Later, back home, you hang your coat by the door and the smell rises again, stubborn and familiar. You wash your hands twice, scrub your face, but the ocean that mixed with concrete and diesel remains. It hides in your camera bag, in the fibers of your hoodie, in the grooves of your boots. Days later, you catch a faint whiff while reaching for something in the closet, and you are right back there, standing on a wet concrete floor under humming lights, watching a fish slide across crushed ice as someone’s gloved hands weigh, judge, and move it forward into the city’s bloodstream.

That is the thing the photos cannot capture on their own, the way the market follows you home. The pictures show the cold, the steel, the ice, the faces, the flag, the trucks. But the smell is the real proof you were there, the lingering evidence that you stepped briefly into a world that runs at a different hour, in a different temperature, by a different logic, and carried a small piece of it back with you whether you meant to or not.