The Healing Strings of Karachi

Where Melody and Medicine Come Together

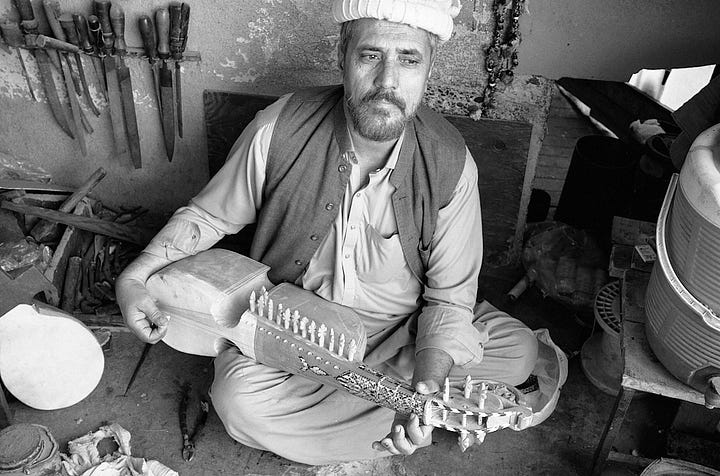

In a quiet alley of Karachi, far from the roar of rickshaws and bustling street traffic, a man tends to two sacred crafts under the same roof. He is both a master rubab maker and a traditional healer, a singular artisan-physician whose hands serve as instruments of healing in more ways than one.

The rubab, a lute-like instrument of Afghan origin, rests gently in his lap. Its wooden body, adorned with intricate mother-of-pearl inlay, reflects centuries of migration, memory, and music. Each instrument he crafts is not merely an object but a vessel, one that carries the stories and sufferings of displaced peoples and gives their experiences voice.

His workshop exists in the minimal space between music studio and healing sanctuary. Locals quietly visit him for treatments passed down through generations, herbal remedies, pressure-point techniques, and therapeutic touch that modern clinics have forgotten. He wraps bandages with the same precision he uses to string the rubab. He listens not only to physical pain but to its history, whether bodily or spiritual.

What distinguishes this man is his philosophy: music and medicine are not separate vocations but twin expressions of the same healing art. One soothes the body; the other mends the soul. In a city where modernity threatens to erase ancestral wisdom, his practice represents a form of resistance, a testament to care rooted in tradition rather than profit.

Between the carefully arranged herbs and half-finished instruments hanging from the walls, he moves with purpose and grace. His patients become listeners; his music students find themselves healed. The boundaries between his roles blur as naturally as the melodies that drift through his doorway into the bustling streets beyond.

In a place where survival often silences art and illness frequently meets indifference, he offers both melody and medicine, practiced with the same reverent hands and dispensed with equal devotion to those who seek either sound or solace, or sometimes both.

Very beautiful piece